We’re interrupting our “Ancestors of Secretariat” series to take a moment to remember the visionary founder of Meadow Stable, Christopher T. Chenery. He died 40 years ago on January 3, 1973 at the age of 86. The man who created “an empire built on broodmares” in Caroline County, Virginia, never lived to see his greatest horse win racing’s greatest prize – the Triple Crown – on June 9, 1973. And now, as we prepare to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Secretariat’s historic victory, it seems fitting to pay homage to the man who set it all in motion.

We’re interrupting our “Ancestors of Secretariat” series to take a moment to remember the visionary founder of Meadow Stable, Christopher T. Chenery. He died 40 years ago on January 3, 1973 at the age of 86. The man who created “an empire built on broodmares” in Caroline County, Virginia, never lived to see his greatest horse win racing’s greatest prize – the Triple Crown – on June 9, 1973. And now, as we prepare to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Secretariat’s historic victory, it seems fitting to pay homage to the man who set it all in motion.

Chris Chenery evinced a passion for horses starting in early childhood. Perhaps it began in 1888 when his father Jimmy Chenery lifted him aboard a horse as a toddler at The Meadow, the family’s ancestral homeplace owned by their cousin, Mary Ann Morris. Chris spent many happy summers there, riding over the fields and by the brambly riverbanks on a borrowed horse.

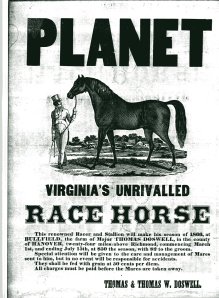

Later, he would walk seven miles from his house in Ashland to exercise the Thoroughbreds owned by his cousin Bernard Doswell at his farm at Bullfield, once a legendary racing stable. There, young Chris soaked up the lore of Bullfield’s glory days and admired the gleaming trophies won at tracks from New York to New Orleans. It inflamed his imagination and quite likely set the stage for what was to come.

The horse-crazy boy grew up to become an accomplished horseman, teaching equitation for the U.S. Army during World War I. Rising from humble roots, he became a self-made millionaire in the utilities industry. Finally achieving financial security for his family, he could indulge his passion for horses further. Robust and vigorous, he played polo, foxhunted and even started his own riding club, Boulder Brook, in Westchester, New York.

But Chenery longed for more. In 1936, he made a decision that would forever change his life, his family’s life and the sport of horse racing. In the middle of the Great Depression, he went back to Virginia and bought back The Meadow, which had been sold out of the family in 1912. As a man accustomed to shaping his own destiny, Chenery was determined to restore and reshape the dilapidated property into his vision of a first-class Thoroughbred horse farm and racing stable.

Once he rebuilt the farm, he set about building up his foundation stock. Known to have “an eye for a mare,” Chenery purchased well-bred but affordable broodmares. Several of them, such as Hildene, Iberia, Imperatrice and her daughter, Somethingroyal, became some of the most influential broodmares of the 20th century.

By 1950, Chris Chenery and his upstart Meadow Stable produced Horse of the Year, Hill Prince. Hill Prince won the Preakness and several other notable races that year, but ran second in the Kentucky Derby. For the man who seemed to possess the golden touch in all his pursuits, Chenery would find winning the golden trophy of the Kentucky Derby his most elusive goal.

He sent two more Derby favorites to the post: First Landing in 1959 and Sir Gaylord in 1962. First Landing finished third and Sir Gaylord broke down before the race. Cicada, the favorite for the fillies’ race, the Kentucky Oaks, in 1962, could have run in the Derby after Sir Gaylord was injured. However, Chenery kept her in the Oaks, which she won handily.

Not until 1972 did Chris Chenery’s dream of breeding a Kentucky Derby winner finally come true. Riva Ridge, by First Landing, avenged his sire’s defeat and brought home the roses for Meadow Stable. But by this time, Chenery was not in his customary box seats at Churchill Downs. He lay mute and immobile, confined to a hospital bed in New Rochelle, felled like a giant timber by the ravages of Parkinson’s disease and what was then called hardening of the arteries. When the nurse pointed out his daughter Penny in the winner’s circle with Riva, a tear rolled down his withered cheek.

Penny had taken over management of Meadow Stable when her father fell ill in the late 1960s. Over the protests of her family, she vowed to keep racing the horses and to keep her father’s dream alive. “At least he knew,” she has said about Riva winning the Derby.

Of course, the next year in 1973, Secretariat, who was born and raised at The Meadow, took Chenery’s dream to heights no one imagined. Secretariat, the first Triple Crown winner since 1948, broke the track records for the Derby, Preakness and Belmont, the only champion to ever do so. Together he and Riva Ridge won five of six consecutive Triple Crown races in 1972 and 1973, something no other stable had done.

The bloodlines that Chris Chenery established for Meadow Stable produced 43 stakes winners. Most outstanding were:

Hill Prince: 1949 Champion two-year-old colt; winner of 1950 Preakness; 1950 Champion three- year-old colt; 1950 Horse of the Year; 1951 Champion handicap male; elected to Racing Hall of Fame

First Landing: 1958 Champion two-year-old colt

Cicada: 1961 Champion two-year-old filly; 1962 Champion three-year-old filly; 1963 Champion handicap female; elected to Racing Hall of Fame (additionally she ranked as the top money-winning female for nine years)

Riva Ridge: 1971 Champion two-year-old colt; winner of 1972 Derby and Belmont; 1973 Champion handicap male; elected to Racing Hall of Fame

Secretariat: 1972 Champion two-year-old colt; 1972 Horse of the Year; winner of 1973 Triple Crown; 1973 Champion three-year-old colt; 1973 Champion turf male; 1973 Horse of the Year; elected to Racing Hall of Fame

Additionally, the great mares Hildene, dam of Hill Prince; Iberia,dam of Riva Ridge; and Somethingroyal, dam of Sir Gaylord and Secretariat, were named Broodmares of the Year. Sir Gaylord, after his pre-Derby injury, distinguished himself as a sire of international importance through his best son, Sir Ivor.

Today, Chris Chenery’s legacy lives on. Many of racing’s brightest stars in the 21st century can trace their bloodlines back to Secretariat, who became a great broodmare sire. His daughters such as Weekend Surprise, Terlingua and Secrettame produced such outstanding sires as A.P. Indy, Storm Cat and Gone West. The progeny of those stallions – think Smarty Jones, Bernardini, the late Pulpit and his son, Tapit, for example – have further distinguished themselves in the sport.

And so we celebrate Chris Chenery, the “Virginia gentleman” as sportswriters called him, whose dream turned into an American legend!

NOTE: Look for our upcoming post on Penny Chenery, who celebrates her 91st birthday later this month and has kept the legacy of her father and Secretariat alive for over 40 years.

by Leeanne Ladin

co-author of “Secretariat’s Meadow – The Land, The Family, The Legend” and “Riva Ridge – Penny’s First Champion”

In our book “Secretariat’s Meadow,” Chris Chenery’s granddaughter, Kate Chenery Tweedy, chronicles how her grandfather’s driving ambition lifted him from humble beginnings to the heights of corporate America and into the top tiers of Thoroughbred racing. You can order the book at www.secretariatsmeadow.com